Is Double/Triple/Whatever Extortion Working?

TL;DR: Probably not, in most cases

I think sometimes we in security fall into the trap of mythologizing adversaries. We think that because cybercriminals do one thing very well, they must be good at everything. It turns out, they often aren’t and ransomware is one of those areas where we have to be especially careful. Ransomware groups are good at one thing: creating ransomware and infecting people with ransomware, that doesn’t mean that the people behind ransomware groups are particularly brilliant. I’ve been involved in enough ransomware IR cases to see what happens when some ransomware actors are forced to go off-script and how much they have to fumble around to know that often they are more lucky than brilliant.

Back in 2019 Baltimore was hit with the Robbinhood ransomware and refused to pay the ransom. The actor behind Robbinhood was NOT happy and took to an underground forum and Twitter to mock the mayor of Baltimore and release documents claimed to have been stolen during the attack. It, of course, did not work. Baltimore still refused to pay the ransom. But, it did help keep the ransomware attack on the front page even longer and may have added pressure on the city to pay.

As always with tactics like this, other ransomware actors picked up on and copied this idea. Most notably, MAZE ransomware was the first to create an extortion site rather than just dumping data in underground forums. Extortion sites are now commonplace amongst ransomware groups. In fact, when a new group is discovered one of the first things that researchers (and journalists) want to know is: what is the URL for their extortion site.

Extortion sites have helped drive awareness of the ransomware problem, seeing all of the victims posted to extortion sites and how frequently the sites are updated helps bring focus to the scope of the problem (even though only a small fraction of victims ever have data posted to extortion sites). Extortion sites also bring infamy to various ransomware groups. These sites give journalists and researchers a chance to communicate directly with ransomware groups (when those groups feel like talking), they also serve as a platform for ransomware actors to release statements or issue press releases.

But, do extortion sites actually help ransomware groups make more money? Maybe they worked initially, but now that organizations have seen that there is no financial consequence for have your data published on one these extortion sites, what is the incentive for most organizations to pay? If a victim is not going to pay to decrypt their files, there really isn’t a reason to pay to get those files taken down from an extortion site.

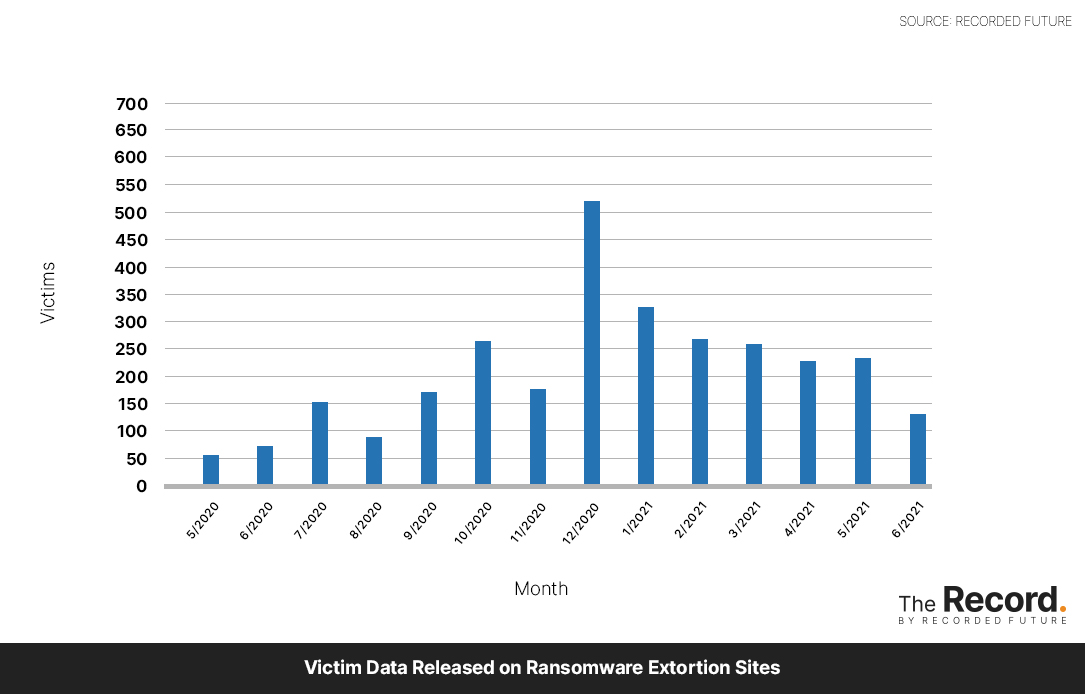

Ransomware groups are starting to realize this. Fewer victims are having data posted to ransomware extortion sites [Full disclosure: Adam used my research in his story] despite the fact that ransomware attacks are up this year. You can see from the chart below that the number of victims posted to ransomware extortion sites in June was the lowest since September of 2020. Again, we aren’t seeing a slowdown in ransomware attacks and, to the best of my knowledge, we aren’t seeing an increase in the percentage of victims paying the ransom it’s just that the threat of “double extortion” doesn’t carry as much weight as it did.

One exception to this guidance, appears to be healthcare. There have been a number of healthcare providers who appeared on extortion site only to be removed shortly after and there was the absolutely sickening blackmail of Vastaamo patients (though, that was not a ransomware attack).

Prior to the REvil shutdown, Valéry Marchive had noted a slowdown in their extortion site publishing. Instead of weeks between an attack and publication it was now often taking months. This could have been a sign of disorganization amongst the REvil group, or it could be that they figured out “double extortion” wasn’t working and they were taking more time to cajole victims into paying.

Finally, there is the expansion of the extortion ecosystem. Ransomware groups using call centers to notify victim’s customers or threatening DDoS attacks or releasing sensitive data on executives. At first these might seem like an escalation of an effective strategy, but if the strategy was working why would they need to escalate? I think that, with rare exceptions, double/triple/whatever extortion is not as an effective tactic as ransomware actors (and many of us) first assumed. Which is why it is as much of a mistake to assume your adversary is a super genius as it is to underestimate them.